Will Capsule Networks Replace CNNs?

Introduction

Geoffery Hinton and his colleagues published a paper entitled by Dynamic Routing between Capules which introduces what is called “Capsule Networks” (CapsNets). In the deep learning community, this is an open for a big wave of research since it is a new neural architecture and might have a great impact. But wait? Why we need capsule networks if we have CNNs? In this blog post, I am going first to discuss the main problems of CNNs, then I will move into the capsule theory by discussing how capsules work and the main algorithm, the Dynamic Routing algorithm, behind this theory. Then, I will go over the CapsNet architecture by explaining its layers and finally we look up at some experiments and results.

I wrote a detailed report and code about this topic so you can take a look for more details.

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

As we all know, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the state-of-the-art models for different tasks in Computer Vision such as object recognition, object segmentation, etc. The intuition behind them is that if we extract first low-level features, then later these features can be combined to build more complex ones. Let’s describe briefly the main layers of a CNN:

-

Convolutional layer: In this layer, given an image as input, each neuron/filter looks at a local spatial region to extract features and map it to a lower space. For example, these filters can be for horizontal lines, vertical lines, etc. The result is a stack of simple feature maps that are used later through the layers to build more complex feature maps.

-

Activation layer: After the convolutional layer, a non-linearity function is applied such as ReLU, where ReLU(x) = max(0, x), in order to add some non-linearity to the system so that more complex relations can be learned between the data.

-

Pooling layer: In this layer, the output of a feature map at a certain location is replaced with a summary statistics of the neighbours. For example, the max pooling operation returns the maximum output between the pixel intensities of a specific region. It is used to remove “unnecessary” information so that the size of the feature maps is reduced to improve efficiency. However, this leads to the loss of the spatial location information which might be important and that is what Capsule Networks tries to tackle and argues that CNN is not doing what we want.

-

Fully connected layer: Neurons in this layer have weight connections to all the activations in the previous layer. So, for a classification problem, each final neuron represents a class and a softmax layer can be added to get a probabilistic interpretation.

Before you continue reading, I think it is really important to understand how CNNs work for understanding capsule networks better and so If you feel you need to learn more about CNNs, I recommend you to check this course from Stanford.

CNNs Drawbacks

Now you might ask what is the motivation behind Capsule Networks? What is wrong with CNNs?

- Spatial relationship between parts

![Figure 1: For a CNN, both images will be recognized as faces. Source: [6]](/images/Capsule-Networks/unnormal_face.png) |

If we look at the two faces above, the right one does not look normal and so we won’t recognize it as a face right? The reason behind that is that we know that the positions of the parts is not correct (in particular the mouth and the eye) and so it shouldn’t be recognized as a face. However, for a CNN, both images will be recognized as faces! Because of the pooling layer, the spatial relationship between parts of the image is lost and so the only thing that CNN cares about is that if the parts are found in the image.

- Rotational Invariance

Another problem in CNNs is that they don’t capture the geometric interpretation of the objects they are detecting. If we have for example a rotated object in an image, then CNN will output that this object exists and not as a rotated object specifically. Again the reason behind that is because of the pooling layer.

![Figure 2: CNN fooled with rotation. Source: [5]](/images/Capsule-Networks/rotate_face_fool.png) |

As an example, the image in Figure 2 is expected to be recognized as a face but when it is rotated and fed to a CNN, the output is a “coal black color” which is totally opposite to what we expect.

Capsule Theory

Definition of a Capsule

After talking about the problems of CNN, let’s discuss now what are capsules and how they work. Before getting started, keep in mind the main problems of CNN so that you can see how capsules may solve them. According to Hinton, Capsule networks do, in a certain sense, what is called inverse graphics. So, given an image as input, we want to find a way to get the instantiation parameters (pose, orientation, etc) of the objects in the image which might help us in the recognition task and give us more information about the objects we are detecting. Capsules are group of neurons/scalars represented by an activity vector. The activity vector encodes the instantation parameters of the object being detected by the capsule. The length of this activity vector represents the probability that the object being detected is present in the image. In other words, each state or dimension of the vector encodes a specific parameter such as rotation, orientation, thickness, lighting, etc.

![Figure 3: Capsule representation. Inspired from [4]](/images/Capsule-Networks/capsule_rep.png) |

In Figure 3 above, the blue arrows represent capsules trying to detect a face. The direction of the vector represents the orientation of the object it is detecting. As you can see, the most left vector is the longest one, which means that the capsule is sure with high probability that there exists a face in this area in addition to its orientation. The other vectors have low probability for the existence of a face. In addition, if the face rotate in the appearance manifold in some direction, then the length of the vector will still be the same because the capsule is still sure that the face exists but its direction will change.

Note that here for simplicity, we have 2D vectors but usually to capture more params, high dimensional vectors are used.

How does a Capsule work?

Previously, the output of a neuron was a scalar but now more information need to be stored and so the output is instead a vector. The following are the computational steps of a capsule.

1. Transforming matrix multiplication

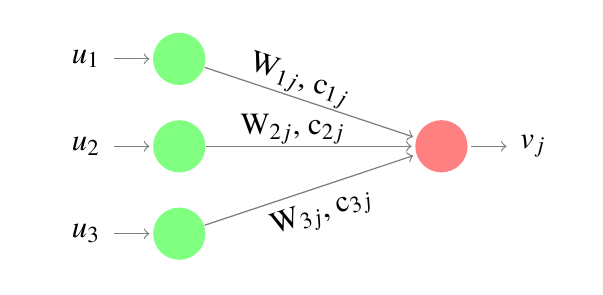

|

In Figure 4, there are 3 input activity vectors or capsules (green circles) that come from the layer below which detected some low-level features. They encoded their probability of existence and their state (pose, orientation, etc). These vectors are then multiplied by a transformation weight matrix W, which represents the spatial relationship between low-level and high-level features. For instance, assume that the 3 capsules had detected 3 low-level features of a high-level object such as a face (capsule represented by the red circle) which are eye, nose, and mouth represented by \(u_1, u_2,\) and \(u_3\) respectively. Then, for example, matrix \(W_{1j}\) may encode the relationship between the eye and the face such as the width of the face is equal to 3 times the width of the eye. The same intuition follows for the other features. The result of this transformation is a prediction vector for the position of the face in relation to the positions of the low-level features. If the prediction vectors are a good match, then the features detected by these capsules are in the right spatial relationship and so they can vote to predict the pose of a face. That is one of the advantages of capsules by allowing the neural network to recognize the whole image by recognizing its parts. The prediction vector from each capsule \(i\) to each capsule \(j\) is denoted by \(\hat{u}_{j \vert i}\) where \(\hat{u}_{j \vert i}= W_{ij} u_i\).

The \(c_{ij}\) coefficients are called “coupling coefficients” and what you need to know about them just for now is that they are used to weight the prediction vectors of the low-level capsules with respect to how these low-level capsules are related to the high-level one. I am going to explain more about them in the following steps.

Each low-level capsule transform its activity vector to a prediction vector by a transformation weight matrix to be used for the prediction of the high-level activity vector.

2. Scalar Weighting

As we saw in Figure 4, there was only one high-level capsule just for simplicity. However, we usually have more than one high-level capsule and so the question now is how a low-level capsule can decide to which high-level capsule it should send its output to? Here it comes the importance of these coupling coefficients \(c_{ij}\). These coefficients are determined by the “Dynamic routing” algorithm which will be explained later in details but for now, we are going to talk about their intuition.

![Figure 5: Capsules agreement. Inspired from: [3]](/images/Capsule-Networks/agreement.png) |

In Figure 5, each low-level capsule has a weighted coefficient \(c\) connected to the capsule in the higher level. When each low-level capsule computes its output (prediction vector), it needs to decide to which capsule in the higher level it should propagate it to. This decision will affect the coupling coefficient \(c\) which is multiplied by its output before sending it to its parent (high level). Now, the high-level capsule already received some input vectors from other low-level capsules. Then, with reference to Hinton’s speech, imagine there exists a vector space for each high-level capsule where the input vectors are represented in it as 2D data points. If there are data points that form a cluster, then the vectors represented by these data points are somehow related to each other (vector similarity). Therefore, when a low-level capsule computes its prediction vector after multiplying its activity vector with the transformation matrix, we check where its data point land in the vector space. So, if it lands near a cluster, this implies that it is related to the low-level features of this high-level capsule and based on that the corresponding parameter \(c\) is updated.

The update of the coupling coefficients is based on an “agreement” mechanism (cluster form) which is the main intuition behind the dynamic routing algorithm

3. Sum of weighted input vectors

This step is similar to normal neural networks which represents sum over a linear combination between the input and the coupling coefficients (weights and neurons).

\[s_j = \sum_{i} c_{ij} \hat{u}_{j \vert i}\]Where \(c_{ij}\) are the coupling coefficients determined by the dynamic routing algorithm. These coefficients represent a probability distribution for the low-level capsule output to which they are sent to high-level capsules. Therefore, we have \(\sum_{j} c_{ij} = 1\) for each capsule \(i\).

4. Squashing (non-linearity)

From the definition of a capsule, the length of its activity vector encodes the probability that the feature its detecting is present and so the length should be between 0 and 1. Therefore, we use a non-linear “squashing” function given by:

\[v_j = \underbrace{\dfrac{\vert\vert s_j \vert\vert^{2}}{1 + \vert\vert s_j \vert\vert^{2}}}_{\text{additional scaling}} \cdot \underbrace{\dfrac{s_j}{\vert\vert s_j \vert\vert}}_{\text{unit scaling}}\]where \(v_j\) is the vector output of capsule j and \(s_j\) is its input.

Dynamic Routing Algorithm

Before digging into the main algorithm behind capsule theory, read again the steps described above if you feel you need to do that because they are the main parts of the algorithm and hopefully as you continue reading, they will become more clear.

![Algorithm 1: Dynamic Routing Algorithm. Source: [1]](/images/Capsule-Networks/dynamic_routing_algo.png) |

Recall that each low-level capsule needs to decide to which capsule in the higher level it needs to send its output to. The coupling coefficients \(c_{ij}\) change with respect to the decision taken and the input of capsule \(j\) will be the output of capsule \(i\) multiplied by these coefficients. Note that they are determined by the dynamic routing algorithm and not learned.

One thing to keep in mind to understand the essence of this algorithm is that it is based on the keyword “agreement.” Low-level capsules “agree” together to activate a high-level capsule.

The following are the details of each line of Algorithm 1:

Line 1: The parameters in the signature are: \(\hat{u}_{j \vert i}\): output of low-level capsule \(i\), \(r\): number of routing iterations, \(l\): number of the current layer.

Line 2: Initial logits \(b_{ij}\) are the log prior probabilities for capsule \(i\) to send its output to capsule \(j\). They are simply temporary variables where at each iteration they are updated, and then their values will be used to update \(c_{ij}\). They are initialized to zero.

Line 4-7: This is the main part of the algorithm. The step in line 4 calculates the coupling coefficient vector for each low-level capsule \(i\) in layer \(l\) \((c_i=[c_{i1}, c_{i2}, ..., c_{ij}])\) by applying a Softmax function. A Softmax function is used because these coefficients have to be non-negative and normalized to have a probabilistic interpretation. Thus, at the first iteration, the entry values of \(b_{i}\) are zeros and so \(c_{i}\) is uniformly distributed (Each entry is \(\frac{1}{K}\) where \(K\) is the number of high-level capsules). For example, if there are 2 capsules in layer \(l\)+1, then \(c_i = [\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}]\) for capsule \(i\) in layer \(l\). This shows that in the beginning, low-level capsules do not know where to send their output to. Moving to line 5, in this step, the output of each high-level capsule is calculated as a linear combination of the input of low-level capsules and the weighted coupling coefficients. In other words, the output is the sum over all the prediction vectors belonging to capsule \(j\) from each low-level capsule \(i\). In line 6, a non-linearity squashing function is applied to make sure that the length of the vector is between 0 and 1. After calculating the output vector of the high-level capsules, the step in line 7 updates the log prior weights. Therefore, for each low-level capsule \(i\), and for each high-level capsule \(j\), the dot product between the input to capsule \(j\) from capsule \(i\) and the current output of capsule \(j\) is computed. The result of this product represents a measure of similarity between the outputs. Then, this product is added to the weights \(b_{ij}\). Finally, the above procedure is repeated r times.

After \(r\) iterations, all the outputs for high-level capsules and the connection coefficient weights are computed.

CapsNet Architecture

CapsNet consists of two parts: An encoder and a decoder. For the encoder, the input is a \(28\times 28\) MNIST digit image and it learns to output ten 16-dimensional instantiation parameters vectors (capsules). Thus, the correct digit corresponds to the vector with the largest length. The decoder has three fully connected layers and tries to reconstruct the original image using the activity vectors of the final capsules. This reconstruction is used as a regularization method to enforce the digit capsules to encode the instantiation parameters.

Encoder

![Figure 6: CapsNet Encoder Architecture. Source: [1]](/images/Capsule-Networks/encoder.png) |

ReLU Conv1 is the first layer of the encoder. It is a standard conv layer that is used to detect simple features to be used later as input to the primary capsules. It has 256 kernels each is \(9 \times 9\) with stride 1 followed by a ReLU activation function. Then, the size of the output is \(20 \times 20 \times 256\) and the number of parameters is \((9 \times 9 + 1) \times 256 = 20,992\).

The second layer is the PrimaryCaps layer which has 32 primary capsules whose job is to learn the combination of the features detected in the previous convolutional layer. To do so, each primary capsule applies \(8\ [9 \times 9 \times 256]\) convolutional kernels with a stride of 2 instead of \(9 \times 9\) kernels. Primary capsules can be seen as convolutional layers with squashing as non-linearity function instead of ReLU. The output volume is \([32 \times 6 \times 6] \times 8\) and the number of parameters is: \(32 \times 8 \times (9 \times 9 \times 256 + 1)\) \(= 5,308,672\).

The final layer (DigitCaps) has 10 digit capsules, one for each digit. Now, as explained before, we have for each 8D vector a transformation weight matrix of size \(8 \times 16\) that maps 8D capsules to 16D capsules. Since there are 1152 8D vectors, then there are 1152 such weight matrices, 1152 coupling coefficients $c$, and 1152 routing logits $b$ that are used in the dynamic routing algorithm. So, in total, there are \(10 \times (1152 \times 8 \times 16) = 1,474,560\) parameters (Note that the c’s and b’s are not counted in the number of parameters because they are determined and not learned!).

Therefore, by summing up the number of parameters at each layer, the total number of parameters is approximately 6.8M. Note that there is routing only between PrimaryCaps and DigitCaps layers. Conv1 layer output scalar value which does not present enough information.

In practice, \([32 \times 6 \times 6] \times 8\) is usually reshaped to \(1 \times 1152\) tensor that represents the low-level capsules. Then, the dynamic routing mechanism takes place between these 1152 capsules and 10 high-level capsules each representing a digit.

Training Loss Function

Recall that the length of the activity vector of a capsule represents the probability of the existence of the object it is detecting. Then, the digit of class \(k\) will have the longest vector if and only if it is present in the input image. The output of DigitCaps is 10 16D vectors. So, during the training, the loss is calculated for every 10 vectors and then summed up to get the total loss. To calculate the loss of each vector, the following margin loss function is used:

\[L_k = \underbrace{T_k\ \text{max}(0, m^{+} - \vert\vert \text{v}_k \vert\vert)^2}_{\text{For correct label}} + \lambda \underbrace{(1 - T_k)\ \text{max}(0, \vert\vert \text{v}_k \vert\vert - m^{-})^2}_{\text{For not correct label}}\]Where \(T_k = 1\) if and only if the digit of class k is present and \(m^{+} = 0.9\) and \(m^{-} = 0.1\). When \(T_k\) is 1, the length of the DigitCaps \(k^{\text{th}}\) vector is subtracted from \(m^{+}\). This means that the loss will be 0 if and only if the probability of detecting the entity by the capsule is greater than or equal to 0.9. Same for the incorrect label detection case, but the loss will be 0 if and only if DigitCaps predicts an incorrect label with a probability less than or equal to 0.1. Moreover, \(\lambda\) is used for loss balance and it is set to 0.5.

Decoder

![Figure 7: CapsNet Decoder Architecture. Source: [1]](/images/Capsule-Networks/decoder.png) |

In the decoder phase, all the digit capsules from the DigitCaps layer are masked out except the correct one. The selected 16D vector is used then as input for the decoder that tries to learn to reconstruct a \(28 \times 28\) image with the aim of minimizing the sum of squared differences between the reconstructed image and the original image. In this way, it helps the capsules to learn the instantiation parameters to construct the original image. This is the same as FC layers in CNN where the \(1 \times 16\) input is weighted and connected to 512 neurons of the next layer. Then, the 512 neurons are connected to 1024 neurons and finally, the 1024 neurons are connected to 784 neurons which can be reshaped to a \(28 \times 28\) image.The total number of parameters is: \((16 + 1) \times 512 + (512 + 1) \times 1024 + (1024 + 1) \times 784 = 1,337,616\).

Thus, Total Loss = Training margin loss + Reconstruction loss

Capsules on MNIST

![Table 1: CapsNet classification results on the MNIST dataset. Source: [1]](/images/Capsule-Networks/capsnet_classification.png) |

Moving to the interesting part which addresses the question how good are these capsules. Well, CapsNet achieved state-of-the-art performance on the MNIST dataset. As seen in Table 1, it scored a test error rate of 0.25\(\%\) using 3 routing iterations and with a reconstruction subnetwork. The baseline is a standard CNN with three convolutional layers of 256, 256, 128 channels and each has \(5 \times 5\) kernels and stride of 1. What is more interesting is that the number of parameters of this baseline is 35.4M, whereas, the CapsNet has only 8.2M parameters and 6.8M without the reconstruction subnetwork.

Capsules Representation

![Figure 8: Capsules representation. Source: [1]](/images/Capsule-Networks/mnist_performance.png) |

To see how capsules are encoding the instantiation parameters of the objects they are detecting, a perturbation can be applied to the activity vector and then fed to the decoder to reconstruct the perturbed image. Figure 8 shows how each dimension of the activity vector encodes a feature about the object and changing it is affecting the reconstruction. This really shows how good capsules are good in encoding these features.

Conclusion

So the questions that might be asked now can we really rely on these capsules? How are they affected by the type of task they are used for? Maybe using capsules instead of CNN can lead to better performance in different tasks such as feature extraction in ASR, images generations with GANs, etc. However, CapsNet is computationally expensive because of the dynamic routing algorithm and there are no experiments yet on the ImageNet dataset. There is always a probability of failure so let’s try to do experiments and see.

Here you can find a code and detailed report about CapsNets.